Once Upon A Time In The Jungle...

She was seventeen years old and she fought with her mom a lot and so it came to pass that Tammy ran off and moved in with her drug dealer boyfriend. And this is where the police found her after the drug dealer's rivals broke into the house and started shooting. They didn't even know who Tammy was, nor did they care. She died to make a point; to punctuate a sentence. And, much as I'd like to tell you this is a scene from Concrete Jungle, the comic book this essay was originally published in, the truth is Tammy, her real name, was a friend of mine. A nice girl from a nice neighborhood who lived in a house on a nice, suburban street and who had a mom and a dad and a cat and a station wagon. She wasn't Shareeka the Jheri Curl Reefer Queen, cracked out and staggering down Fulton Street mangling Busta Rhymes tunes. She was third from the left in the photo I took when our team won the flag at summer camp in 1974. She was Nancy's best friend and, though Nancy was Lucy Van Pelt to my Charlie Brown, Tammy was always kind to me, always my bud. Rustling around somewhere in Priest's Big Bag Of Regrets is the fact I never tried to be more than a friend to Tammy, as though decisions we make could actually stay the hand of an often perplexing God.

If you've never had a .45 automatic aimed at you in anger,

you're really missing something. It looks like the biggest,

blackest, meanest piece of metal ever created by man, and you

suddenly move somewhere to the right of yourself and become a

casual observer; a lowly extra in the film of your own life's

story. You want Tom Cruise, but you get Jon Lovitz. You become

Jon Lovitz as frame after boring frame of your life clicks by

while the guy holding the gun plays keep-away with your dignity.

I grew up in daily mortal fear and with an acute awareness of

where I could and could not go, the difference between the two

being as little as a city block. I’d wake up to the thunder of

jungle drums: idiots who’d literally point giant speakers out of

their windows and start blasting what would later become known

as Hip-Hop music from their homes in a kind of jungle warfare.

It was tribal: the precious little dignity these young boys had

centered around their material wealth or the illusion thereof

created by who had the loudest sound system. These boys filled

their days hanging out on stoops, hustling for beer and reefer

money, playing basketball, and telling lies about sex. You could

tell the guys who were actually having sex from the liars

because the guys actually having sex usually left the jungle

because they got some stupid girl knocked up, just as my sister,

a stupid jungle girl, got herself knocked up. Like we didn’t

already have enough problems. There wasn’t a huge distinction

between life in the jungle and life in the yard at Rikers

Island. All we had was time and far too much of it.

I was terrorized, daily, first and foremost by my own sister,

who escalated sibling rivalry into Josef Mengele-level masochism

and who routinely encouraged and joined in with the neighborhood

bullies who beat and terrorized me just as she beat and

terrorized me. For three consecutive years I never once came in

alone through the front door of my own house, but went out the

back and jumped over neighbors' fences to avoid bad guys and

worse guys. I was afraid to be on the streets, I wasn’t safe at

home because my sister would routinely invite the streets

inside. I mean, I’d come home and find the jungle in my house,

waiting for me, my idiot sister serving these terrorists who

beat me, who robbed our house, snacks and

entertaining them. I spent the majority of my childhood wishing

to be away from these people I lived with. That was my only goal

in life: Get Away From Here. Get Away From Them. I was a little

kid. Their job was to protect me. Neither ever did. I knew,

maybe as early as ten years old, I was completely on my own.

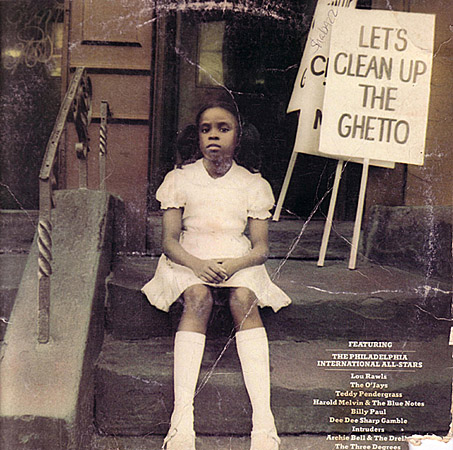

Osama bin Debra:: Philadelphia International All-Stars' Let's Clean Up The Ghetto.

In the jungle you look no one directly in the eye.

You practice invisibility, and the best days are the ones that

pass without incident. There is a casual acceptance among even

the youngest jungle kids that death could come literally at any

moment, and this acceptance becomes license to define their own

morality based on consequence and circumstance.

Mine was a world of bad guys and worse guys, and no matter how

hard I prayed for Superman or Jesus to come and save me, neither

ever did. My father, whom I have never met, lived in the same

borough of the same city but allowed us to suffer winters

without heat and weeks without food. Mom used to make what I

called her famous “Five Day Soup,” a concoction of whatever was

lying around that actually wasn’t bad the first two or three

days you ate it. I kept looking for the man with the white hat

or the man on the white horse to ride to the rescue, but the

reality was my mother, sister and I standing in waist-high snow

waiting for a bus that wasn't coming.

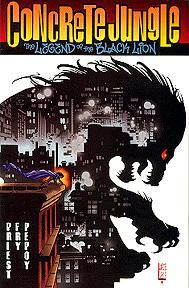

I could easily have become Elijah Book or Terry Smalls or

Freedom "Mayor Bob" Mandela—main characters from The Concrete

Jungle, a series torpedoed by Acclaim Comics’ abrupt demise in

1998. In some ways, I am all of them. As a writer all I do is

report what I've seen and what I know to be true in some

pathetic attempt at self-healing. Jungle, a cynical, dark urban

legend, was born out of a childhood of constant anxiety, a

childhood lacking either safety or security, its joy and rage

and tears and unanswered questions and all that lack of closure

trotted out in metaphors of masked goats and so forth.

Concrete Jungle is an urban fable about bad guys and

worse guys— people moving through the jungle in herds of

collective self-interest. Political activist/huckster Terry

Smalls is visited by an African mystic who informs him he is

heir to a noble legacy. Smalls' conversion puts him at odds with

a massive wheel of corruption, the self-defining morality of the

urban jungle, of which Tammy Rogers’ unsolved murder is the

center hub. Like building a Taco Bell in the Veldt, obtaining

justice for Tammy will be a shock to the jungle's eco system.

Smalls has to struggle with both his own moral weakness and the

question of whether the re-setting of one man's moral compass is

worth the destruction of almost every life he touches— starting

with his own.

As with my actual life, Concrete Jungle is full of evil people

who do wonderfully noble things and good people who benignly

incorporate some level of hypocrisy and corruption. With people

who love without sacrifice. It is ruthlessly, giddily cynical

with a dash of hope tossed in, hope being the most invented part

of the piece. It’s got crime and sex and politics and ancient

mysticism and modern religion, with heaping doses of black humor

and wrenching terror.

And, threaded through the complex layers, it's got what I know

to be true. Just a little piece of it. Maybe that's enough.

Part of the many complex reasons my marriage failed was my wife

failing to convince me to move back there. We lived in New

Jersey at the time but her family still lived in New York.

Moving closer to "home" was the farthest thing from my mind. I

have terrible memories of growing up, of the old neighborhood

and the old faces. Once my mother and grandmother moved to

Florida, I no longer had any reason whatsoever to go there, and

it's been at least fifteen years since I have. This was

something I could never get her to understand: I wasn't being

selfish, this was about survival. If I moved back there, I'd

lose my mind.

I no longer live in the jungle. I live in the

foothills of the Rocky Mountains, in a town where crime is

pretty low, perhaps because the corner drug store sells pistols

and everybody's got a gun rack on their Toyota 1-Ton. Maybe I

just traded one jungle in for another.

Christopher J. Priest

Relatively Jungle-Free

22 February 1998 (Original)

21 November 2011

Home | Blog | Projects | Comics | Rants | Music | Video | Christian Site | Contact

Unless Otherwise Specified, Text Copyright © 2011 Lamercie Park. All Rights Reserved.

TOP OF PAGE