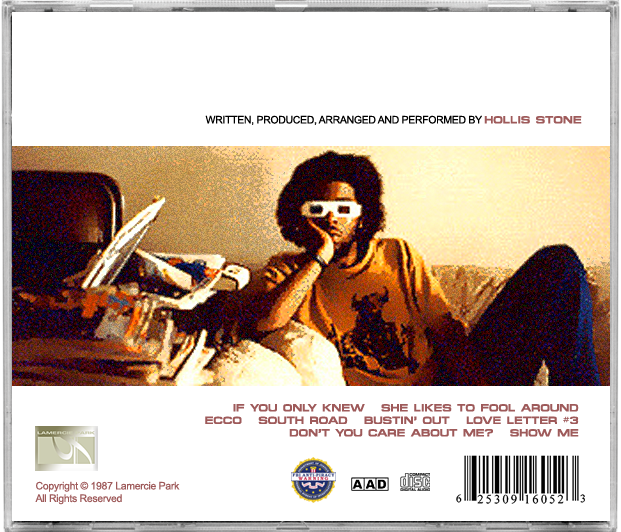

Going Pro

Pandora's Box was, essentially, an update of my demo, Girls. I

was still sort-of pursuing a career as either an artist or, more

likely, a songwriter and/or producer. I existed within the

periphery of the music industry, a face in the crowd of faces

you might glimpse as an actual recording artist passes by. I had

limited access to Warner Bros and to A&M records, who liked my

material and requested more (but with changes and lots of

advice). What I didn't have was a quality demo, and I was now

weighted down with the stupid things young adults pack into

their lives: a new car, nosebleed-high car insurance (over

$2,000, and that was in 1983!), an expensive apartment, a

live-in girlfriend, a long and painful breakup. Updates on my

demo would need to happen at home.

I'd bought a couple of the new, cheap knock-offs of quality

keyboards from Korg, a DW (digital waveform) board that had

the new "modern" sound (very cold and annoying to listen to for

long), and Korg's Poly8 knockoff of the legendary Prophet V.

Along with an old Wurlitzer electric piano I bought from a

friend, my trusty Roland 707 (I couldn't afford the

industry-standard 808), and a very expensive Guild Pilot

bass, these boards formed the core of my one-man band. At

tremendous sacrifice, I bought a Tascam 246 Portastudio, a

massive improvement from the little 244, and mated it to a

Yamaha 1204 PA board, a huge piece of furniture that dominated

whatever room it was in. The tonal quality of the work took a

major jump.

Thanks to Bonita, I was also a much better singer. Still awful, but

not wretched. I was, for the first time, actually paying

attention to whether or not I was in key and to the tone of my

performance, two things I'd virtually ignored previously, as I'd

seen myself as an ersatz Springsteen, a kind of everyman rather

than a polished singer. I was still, by no means, a polished

singer, but, thanks to Bonita's quiet and patient encouragement,

I was at least making some effort toward my singing and not just

throwing it out there in one take and wandering off.

The double entendre title reflected my, and by extension all

straight males', obsession with women which, in a cynically

clinical point of view, is actually the male obsession with a woman's

vagina or, more specifically, controlling access to it. History

resounds with tragic, epic-scale bloody wars fought over some

lunatic's obsession with either his mother or his lover; man's

destiny predicated upon either the vagina he came out of or the

one he is desperate to enter into. All economics, culture, and

even religion (the virgin birth) can be defined by this idea,

which distills even further to the very existence of humanity.

Absent this seminal (pun intended) obsession, the human race

would have died out eons ago. My declaration, here, is the most

deadly weapon known to man is not the atom bomb but the vagina;

a human organ smaller than your hand which nevertheless controls

the fate of the world.

The other half of that equation, of course, is male interaction

with this particular body part can and often does open up a can

of worms or, as in the Greek myth, a magic chest full of evil

woes. The Apostle Paul, whom I do not believe even liked women

very much, warns against engaging with these people in any way

(I Corinthians 7), saying, essentially, "I'm trying to spare you

the trouble that comes from these relationships." The

throughpoint of Pandora's Box was the reeling from one

relationship to the next I did in my younger days and my

wondering what it all meant. What was I actually looking for?

When I imagine all of the time, money, energy, creativity and

investment I wasted, I mean utterly wasted, on this

gender, it makes me suicidal. If most men could get back even a

fraction of the effort they squandered either pursuing or being

dominated by the many women in their lives, the world economy

would be in much better shape.

If You Only Knew, my great pledge of love to the inexplicable

Nancy from 1985, got a facelift here. With the new 1204 board and better

reverb units and, thanks to my work with Bonita, better singing

on my part, the revised version is perhaps the best singing and

playing I’ve done on this compilation.

I fell in love with Yanick at a showcase her band was having at

Sweetwaters on Manhattan’s upper West Side. I knew it was

possible to fall for her, so I had been more or less avoiding

her, but she talked me into coming. Arriving at the club, I

found a panic-stricken Yanick whose bandleader had locked some

of their equipment in the trunk of his car. She put her arms

around me for comfort, fell into my arms, and I fell in love. I

spent the rest of the evening feeling like the world’s biggest

idiot. I met Rachelle at the club that night. Rachelle was closely tied

into Yanick and her twin's orbit, but I didn’t realize it at the

time. Yanick was still seeing this other guy, and I, anxious to

not be in love with her, pursued Rachelle into something that

felt a lot more like a stock transaction than a romance. I really liked her, I really wanted

the relationship to be more than it was. I was still The Man Who

Knew Much, Much Too Little. The Man Who Was Lied To By Literally

Everyone He Ever Met. And, in retrospect, Rachelle was right. I

got it wrong.

She Likes To Fool Around was originally written as a gag record

for her, a biting poke in the ribs at

someone who, essentially, wanted a pretty shallow relationship

with me—a man whose passions ruled his life most of the time.

After a particularly stupid incident involving her sister, we

parted company, and the song went from being a private pun

between us to a mean-spirited indictment of her value system (or

lack thereof). Here I perfected The Prince Scream, and there’s

some pretty good playing here if you consider the fact I had no

sequencers or samplers.

Grown-Up Girls

In the summer of 1987, my mother decided to move to Florida,

and Derek Burch helped me move her. Before we left, we holed up

in Hidden Lake to re-record some tunes I’d been working on.

Post-Bonita, my confidence in my own singing and my own value as

an artist was shaky at best, but I’d felt there was enough

growth to warrant an update on my demo. Derek, the good friend,

the generous-to-a-fault and loyal pal, happily gave up a long

weekend (to the chagrin of his wife who called every ten minutes) and, like two frat

brothers, we spent a glorious long weekend recording

Ecco and South

Road. We traded off engineering tasks, which was a great relief

to me. Typically I have to run the board and perform at the same

time, which meant every take took three times as long as it

would if I had an engineer. That weekend was the only time I

actually had an engineer, and things came together very quickly.

Later I recruited Bonita to flesh out the backgrounds, and she

graciously volunteered. Oddly, she couldn’t get the close

harmony on Ecco: do you really know what you’re lookin’ for?

Every time you hear that line in the song, that’s all me,

dubbing myself over about six times. The rest is me and Bonita.

Ecco was a woman I'd met at a skating rink to whom I began giving

rides home at night. I’m sure I wanted to date her, and I

originally wrote the song Ecco as a means to impress her.

In retrospect, this actually never worked. The women I was

meeting really could not appreciate the craft that went into the

music. The majority of those songs, which took me upwards of 30

hours to produce, were never listened to.

Ecco turned things around on me and treated me like a geeky

schoolboy, even setting up the rink DJ to publicly ridicule the song and

myself. Maybe I had it coming for being such a poor judge of

character. Ecco was shallow and truly ghetto and I have

absolutely no idea what I was thinking.

Ecco was a woman I'd met at a skating rink to whom I began giving

rides home at night. I’m sure I wanted to date her, and I

originally wrote the song Ecco as a means to impress her.

In retrospect, this actually never worked. The women I was

meeting really could not appreciate the craft that went into the

music. The majority of those songs, which took me upwards of 30

hours to produce, were never listened to.

Ecco turned things around on me and treated me like a geeky

schoolboy, even setting up the rink DJ to publicly ridicule the song and

myself. Maybe I had it coming for being such a poor judge of

character. Ecco was shallow and truly ghetto and I have

absolutely no idea what I was thinking.

Years later, my mother called me in a panic looking for my

sister, who suffering from a substance abuse problem. I went

door to door looking for her, going from one crack house to

another until I finally found her, late one night, huddled in a

basement. I looked at her and offered my hand, saying, “You

don’t have to live like this. You can walk out of here with me

right now.” She opted to stay. These were

lessons she’d have to learn on her own.

I re-fit

Ecco into a plea, a love song, to my sister. South Road

was a nasty strip of burnt out stores in South Jamaica where

people typically went to score and shoot up. My sister didn’t

actually live on South Road, but I have no doubt she knew where

it was.

I took a fresh pass at the vocals and mix on

Bustin' Out, also

from Girls. It was still not a great vocal performance and a really bad

recording, but Qabid simply loses his mind on the bass (playing

my Guild Pilot), and Glen Alexander melts the paint off the wall

with his amazing Slash-style metal guitar assault.

Love Letter #3 was written for Rachelle and sent to her during a

particularly down period in her life. She seemed annoyed by it

and kind of blew it off. I’d committed a kind of cardinal sin:

caring about her. It sent the relationship into a spiral and

never really recovered. Like I said, I got it wrong. Years

later, I now realize Rachelle was probably the most honest and

healthy relationship I’ve had.

This song also marked the introduction of my new Yamaha 1204

mixing board. It was, and still is, a huge piece of real estate.

A 12x4x2 [+4] board, I had to use all of these step-down

transformers so the XLR [+4] outs could talk to the RCA [-10]

inputs on my Tascam 246 4-track cassette deck. It was a really stupid choice for a recording console

(it’s actually a P.A. console), but it had tons of headroom and

was exceptionally clean. The production values in my little

studio shot way up, as I clumsily learned how to use the board

by trial and error. Mostly error.

This song also marked the introduction of my new Yamaha 1204

mixing board. It was, and still is, a huge piece of real estate.

A 12x4x2 [+4] board, I had to use all of these step-down

transformers so the XLR [+4] outs could talk to the RCA [-10]

inputs on my Tascam 246 4-track cassette deck. It was a really stupid choice for a recording console

(it’s actually a P.A. console), but it had tons of headroom and

was exceptionally clean. The production values in my little

studio shot way up, as I clumsily learned how to use the board

by trial and error. Mostly error.

Love Letter #3 was one of the first songs I attempted to record

in stereo, no easy task when you’re dealing with serious low-end

4-track stuff. Reading up on Bruce Sweiden’s “Acusonic” process,

I stumbled onto the concept of half-speed mixing. This involved

flipping a switch on my high-speed Tascam 246 4-track so it

would play back at half-speed, and mixing down the 4 music

tracks to a stereo mix on another DBX deck. Then I would take

the new tape, put it in the 246, flip the switch back to high

speed, and have a clean mix of the music tracks with virtually

no noise and little generation loss. Then I’d bounce vocal

tracks, building a choir or whatever I wanted back there, and

all of it super clean and quiet.

My close friend M.D. “Doc” Bright played bass on

Love Letter #3,

complaining bitterly about everything, the way he does.

Don’t You Care About Me? was my great declarative statement to Yanick, sent to her sometime in 1988. Doc played bass on this one as well, and

I’d recruited my neighbor’s son to sing lead on this originally,

but later erased him and tried it myself. I believe Don’t You...

was the last song recorded on the old PortaStudio, as I’d just

bought the nosebleed expensive Tascam 246 high speed deck.

Show Me was actually recorded, I think, in 1986 but I kept it,

as is, here on the ‘87 demo because of its honesty. It is the

most honest piece of music I’ve ever done; my final,

heartbreaking plea to Nancy.

These tracks, from my

Pandora’s Box

demo, earned me some

attention from a couple of record labels, culminating with a

meeting at the short-lived Motown label Apollo Theater Records.

Sitting in the offices, listening to an over-hyped A&R team pitch

ideas and try and force a severely unlikely paring between

myself and some other coked-out producer, something died inside.

My desire, my entire appetite for the music business, vanished.

I think I walked out of there agreeing to some follow-up

meeting, but never showed up and never returned their calls.

I never wanted to be a star in the first place. I just wanted to

make a living playing my songs and ministering to people. I

wasn’t willing to play the game, to kiss enough backside and

smile at these egregiously vituperative jackals grinning at me

across the desk. I also had a sudden fear of becoming Michael

Jackson, and not ever being able to go to the 7-Eleven again.

I considered starting a local label and doing my own local

distribution, like Larry Norman, a Christian rock artist (some

say the originator of the art form), and my role model. I tossed

Pandora’s Box on the big stack of tapes and went on with my life.

Christopher J. Priest

January 2000 UPDATED OCTOBER 2013

Home | Blog | Projects | Comics | Rants | Music | Video | Christian Site | Contact

Unless otherwise specified, Copyright © 2013 Lamercie Park. All Rights Reserved.

TOP OF PAGE